‘Una Chicana’

Mexican American student speaks about disconnection from culture, heritage

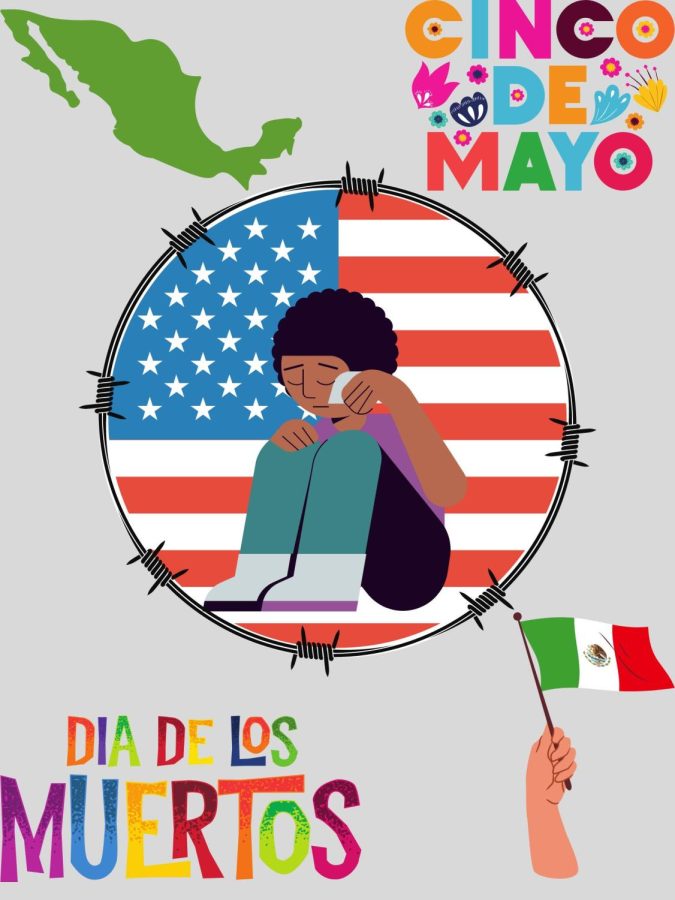

Mexican Americans that grow up in the U.S.can feel disconnected from their Hispanic roots when their parents don’t teach them their native Spanish language or about their culture and history.

February 1, 2022

She walked into her History class. She greeted her teacher and made her way to her seat. As she readied her paper to take notes, she glanced at the board and her stomach immediately sunk to the floor. She felt the eyes of her classmates lock on her. Tears threatened to rush down her cheeks and soak her paper. As quickly as she could move, she buried her head in her hands. This couldn’t be happening. This is so embarrassing. The whispers of her peers were echoing in her skull. “She is a Mexican. Let’s ask her.” The teacher made his way to the front and loudly exclaimed, “Okay students, today we are going to take notes on the influence of Mexican history on 1700s America.”

She wanted to be anywhere but in that classroom. As a Mexican American, she should be excited to discuss the history of her motherland, but when she sees the Mexican flag photo on the board, she feels nothing but shame.

Shame on her for not knowing Spanish.

Shame on her for not knowing any Mexican Traditions.

Shame on her for wanting to get rid of her ethnic features; Shame, Shame, Shame.

“I’m not a Mexican,” she said. “I am a failure.”

She peered through teary eyes at the board and saw a photo of an Indigenous Mexican tribal chief. As her eyes traced down his hooked nose, prominent cheekbones and strikingly dark eyes, she ran her hand down her own face and felt how similar they were. How could she possibly share features with a proud, strong Mexican, when she herself had never left America.

She stayed that way for the rest of class, head on the desk, crying. She felt the weight of the thousands of her ancestors staring over her shoulder, disappointed that she had failed to uphold all that they worked so hard to create.

Senior Jessie Gonzales is a Mexican American who has a complete separation from her culture despite her entire family being Mexican.

“That’s like an iffy thing, because the only time that they do speak Spanish is when they don’t want us to know what they are talking about,” Jessie said. “So, my step dad is fluent in both English and Spanish, and my mom can’t speak it. But she can understand it, so you can have a conversation with her. The minimum I can speak is ‘hello’ and ‘how are you?’.”

Through her early childhood she knew her ethnicity, but had no idea where her bloodline came from.

“I grew up knowing that I was Mexican American,” Jessie said. ‘Una Chicana’, which is a person who is of Mexican descent, but grew up in America only. I never understood why people called me that until my parents explained it to me. So I would get called ‘una chicana’ during elementary school.”

Throughout her school career, she was harassed by Caucasians and Mexicans alike.

“I can’t hide it, because when you look at me, you can just see that I am Mexican,” Jessie said. “It really hurt, because when they would speak Spanish around me, I would never know if they were talking bad about me or not. Then being in a Spanish class full of Caucasian people, they would always ask me ‘Hey what’s this word?’ And it was really embarrassing to have to say ‘I don’t know. They assumed because I am Mexican that I should know Spanish. It is a hurtful stereotype.”

As she moved to and from multiple states in the U.S., she was surrounded by lots of different types of people, but it was still hard to relate with her fellow Mexican Americans.

“I grew up in six different states,” Jessie said. “California was very mixed, but then Iowa, Nebraska, and those were only white people. I didn’t have an issue making friends, but culturally it was easier to relate with the white people.”

Gonzales admits her envy for Mexicans who speak Spanish and know their culture, and expresses her longing to be accepted by them.

“It is so embarrassing,”Jessie said. “My parents’ coworkers speak only Spanish, and one time they wanted to meet me and my sister. We just had to stand there and awkwardly smile. Also when I was younger, I couldn’t speak to my grandmother, but she and I would sit on the couch and watch Mexican television shows. She would laugh and cry, but I never understood a word.”

Images of Mexican culture bring tears to Jessie’s eyes as she feels like she is locked out of her heritage.

“I am also part of Yaqui an indigenous tribe in Mexico,” Jessie said. “When I see them all dressed up with their hair done, I feel sad in my soul. I feel isolated, like my life is in a bubble, and I am watching everyone else enjoy a culture that I am supposed to be a part of. When I listen to Selena, I feel so close to her and myself because she was also from Texas. She didn’t know Spanish as a child, and she only learned the Lyrics to Spanish songs so she could sing with her family. She actually never became fluent in Spanish, and she was so loved and accepted by Hispanics everywhere. So, why can’t I.”

Jessie plans on reconnecting with her heritage more as she gets older.

“A DNA test would help a lot to see what I am,” Jessie said. “I do want to visit the places where the Yaqui were–where my people were from. Seeing it and learning more about it, I am just like wow! I am a part of that. I didn’t even know until recently that people with indigenous blood can join the existing tribes by having a certain percentage of blood connection.”

There are over 5 million Mexican Americas who do not speak Spanish and report feeling a separation from their culture. Jessie hopes to lend some advice.

“Get a DNA test,” Jessie said. “ Just in case your parents try to lie to you or if you just feel like something is not quite right. Emotionally, it can stand as proof of who you are. Just take your time. If you are ever uncomfortable, just slow down. There is no rush. Your blood will never run away from you.”